Coral reef islands may be able to avoid ‘drowning’ this century as seas rise by naturally gaining sandy sediments to stay above the water line, a study shows.

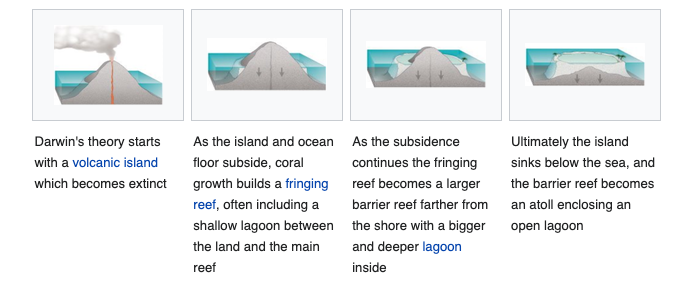

The idea that coral islands can adapt to sea level change is hardly new – British naturalist Charles Darwin explained ring-shaped Pacific and Indian Ocean atolls in an 1842 study as reefs growing upwards around the peaks of ancient volcanoes that were sinking because of natural subsidence.

The new research, led by Plymouth University and published in the journal Science Advances this week, gives experimental evidence of how sand, shingle and other sediments washed onto low-lying islands may help them survive despite accelerating sea level rise.

“Coral reef islands can accrete vertically as sea level rises due to overwash and do not necessarily drown,” lead author Gerd Masselink, Professor of Coastal Geomorphology in Plymouth, wrote in a tweet.

Too often, the scientists wrote, islanders in vulnerable low-lying states from Tuvalu to the Maldives were wrongly presented as facing a stark binary choice – move elsewhere or build massive coastal defences as seas rise.

A third option may be to rely on natural processes by which reefs grow, they wrote.

“Previous research into the future habitability of these islands typically considers them inert structures unable to adjust to rising sea level,” Masselink wrote in a statement.

“It is important to realise that these coral reef islands have developed over hundreds to thousands of years as a result of energetic wave conditions removing material from the reef structure and depositing the material towards the back of reef platforms, thereby creating islands,” he added.

“Overtopping, flooding and island inundation are necessary, albeit inconvenient and sometime hazardous, processes required for island maintenance,” he wrote.

The scientists built a model of Fatato Island in Tuvalu and put it in the Coastal Ocean and Sediment Transport Lab at the University of Plymouth.

The artificial island was pounded it with experiments simulating rising seas, driven by a melt of ice from Greenland to Antarctica. The island’s crest rose, while retreating inland, as waves deposited sediment.

The scientists then used numerical models to see how the island would adjust to a sea level rise of 0.7 metre, the average by 2100 from scenarios by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“During the numerical simulations, the island crest rose by just under 0.7m, showing that islands can keep up with rising level and confirming the laboratory experiments,” they said.

There are still many uncertainties.

Co-author professor Paul Kench, Dean of Science at Simon Fraser University, Canada, said: “It is important to stress there is no one-size-fits-all strategy that will be viable for all island communities – but neither are all islands doomed.”

Last year, Kench led a study that also challenged conventional wisdom about land loss by showing that Tuvalu, comprising’s 101 islands, had gained ground in the last four decades.

It showed “a net increase in land area of Tuvalu of 73.5 hectares (2.9%), despite sea-level rise, and land area increase in eight of nine atolls”.

But those findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, were based on a rise in sea levels around Tuvalu of about 15 cm over the 40-year period, less than rates projected for this century if emissions rise.

Main photo: Islands in the Maldives – where sandy or gravel islands sit on top of coral reef platforms – are among those that could be affected by a global rise in sea levels Credit: Gerd Masselink/University of Plymouth

Darwin’s 1842 theory: