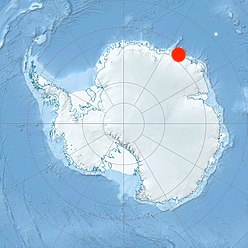

A remote glacier is melting surprisingly fast in a previously unknown ‘hotspot’ in East Antarctica, adding to worries about sea level rise from the frozen continent, scientists said on Monday.

Ice beneath the end of the Shirase Glacier was thawing because of a flow of less chilly sea water into the Lützow-Holm Bay, Japanese researchers wrote in the journal Nature Communications.

The report, headlined “Japanese expedition identifies East Antarctic melting hotspot”, adds to concern about the thaw of ice sheets that are raising sea levels amid global warming.

“Our data suggests that the ice directly beneath the Shirase Glacier Tongue is melting at a rate of 7-16 meters per year,” Assistant Professor Daisuke Hirano of Hokkaido University’s Institute of Low Temperature Science, said in a statement.

“This is equal to or perhaps even surpasses the melting rate underneath the Totten Ice Shelf, which was thought to be experiencing the highest melting rate in East Antarctica, at a rate of 10-11 meters per year.”

The Shirase glacier, south of Africa, is named after Nobu Shirase, leader of the Japanese Antarctic Expedition of 1911–12. The Totten Ice Shelf is south of Australia.

Separately, British scientists say the Earth has lost 28 trillion tonnes of ice from 1994-2017, driven mainly by man-made global warming.

According to the article under review for the journal The Cryosphere, the loss of ice on Greenland and Antarctica and in mountain glaciers had raised global sea levels by 3.5 cms in the period.

And the pace of melt has accelerated in recent years.

The Financial Times said in an editorial that “melting ice is a reminder of the climate emergency”.

East Antarctica contains enough ice to raise the world’s sea levels by about 60 metres if it ever all melted, meaning that even thaws around the fringes are a cause of concern to coasts around the world and cities from Shanghai to San Francisco.

Most research into melting ice in Antarctica has focused on the smaller West Antarctic ice sheet, which is more vulnerable to melting but locks up only a few metres of sea level.

The Japanese team, which gained access to the Shirase glacier when sea ice unexpectedly broke up, said that the melting of the glacier tongue “occurs year-round, but is affected by easterly, alongshore winds that vary seasonally.”

“When the winds diminish in the summer, the influx of the deep warm water increases, speeding up the melting rate,” a statement said.

The scientists would build their observations into models for sea level rise. Seas could rise by about a metre in the likely worst case by 2100, according to the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

PHOTO – The Japanese icebreaker ship Shirase near the tip of the Shirase Glacier during the 58th Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition (Credit: Kazuya Ono)