A glacier in Antarctica retreated at 50 metres a day at the end of the last Ice Age, far faster than the current quickest rates and an alarming sign of what might happen in a warming world, scientists said on Thursday.

If repeated, such a pace of ice loss from the frozen continent sea would sharply raise sea levels and perhaps destabilise vast ice sheets inland and quicken their slide downhill into the Southern Ocean.

“Very high rates of grounding-line retreat are possible, greater by an order of magnitude than those reported for ice shelves since satellite observations began,” the scientists wrote in the journal Science. Satellite observations began in the 1970s.

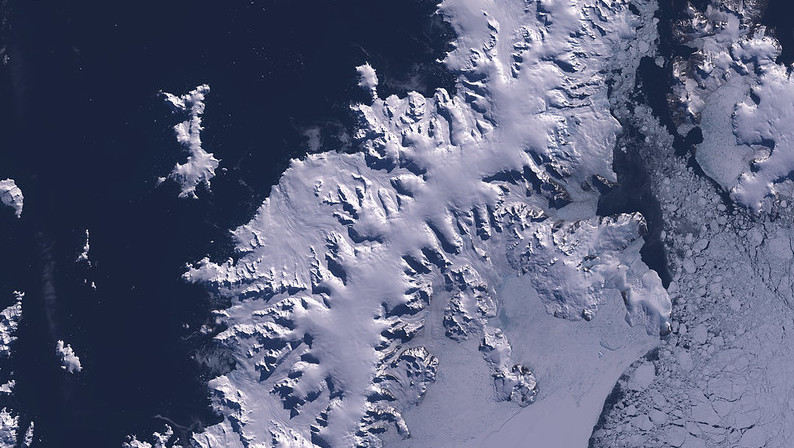

Using a robot submarine, the researchers found delicate seafloor ridges on the Larsen shelf east of the Antarctic peninsula, apparently ancient imprints formed by the near twice-daily tide gently raising and lowering the underside of a vast shrinking glacier onto squishy seabed sediments.

The experts, led by Julian Dowdeswell of the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge, likened the parallel seabed imprints of the glacier’s grounding line at low tide to the rungs on a giant ladder, about 20 to 25 metres apart, giving a daily retreat of 40 to 50 metres.

The rungs were apparently left in a warming period after the peak of the last Ice Age about 14,000 years ago, they wrote in the journal Science. The Earth swings in and out of Ice Ages as the planet’s orbit shifts over thousands of years.

Seas rose about 120 metres in the thaw at the end of the Ice Age but stayed relatively unchanged for centuries before starting to rise amid a build-up of man-made greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere after the Industrial Revolution. Seas have risen about 16 cms in the past century.

Over a year, 50 metres a day would work out at just over 18 kilometres a year. The scientists said the retreat was more likely to be closer to 10 kms, because the ice was likely to retreat so fast in the chill depths of winter.

By comparison, they noted that Antarctica’s Pine Island glacier, now one of the fastest retreating in Antarctica, shrank 1.6 kms a year between 1992 and 2011 in a trend scientists link to global warming.

A vast set of icebergs broke off the Pine Island Glacier, further south than the Antarctic Peninsula, in February. The largest was about twice the size of Washington DC, according to NASA.

Such break-ups, or calvings of glaciers, are natural but have been accelerating in recent years.

Last year, the UN panel of climate scientists said that sea levels worldwide were likely to rise by anywhere from about 30 cms this century, if governments sharply reduce greenhouse gas emissions, to around a metre if the world continues to raise emissions of heat-trapping gases.

Martin Jakobssen, of Stockholm University, said that other patterns – corrugation ridges or washboard ridges – had been studied on other seabeds, but were sometimes ascribed to the keels of giant icebergs bobbing up and down with the tides, not to entire glaciers.

“The precise ice dynamics of this regular mass loss that is paced by tide is not resolved and presents a challenge for the ice-modelling community,” he wrote in a comment in Science.

“Although the mechanical details are yet to be characterised, Dowdeswell et

al. have used the idea that the ocean tide paces the formation of the rungs to convert the distances between the rungs to a retreat rate of the ice sheet,” he wrote.