Climate change is transforming the polar regions and triggering what may be an “irreversible” melt of ice in Antarctica that will drive up global sea levels, authors of a U.N. study of the polar regions say.

Warming of the Arctic region is disrupting the hunting livelihoods of Indigenous peoples as sea ice shrinks and threatening polar bears and other ice-loving wildlife. Some fish stocks are moving north and the region is opening up to more shipping and tourism.

“We see a new environment coming,” said Martin Sommerkorn of the WWF Arctic Programme, one of two coordinating lead authors of a chapter about the polar regions in a U.N. study of the oceans and the Earth’s frozen places issued last week in Monaco.

Surface air temperatures in the Arctic have warmed by more than double the global average in the past two decades, according to the study by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“The polar regions are losing ice, and their oceans are changing rapidly,” the report says. “The consequences of this polar transition extend to the whole planet, and are affecting people in multiple ways.”

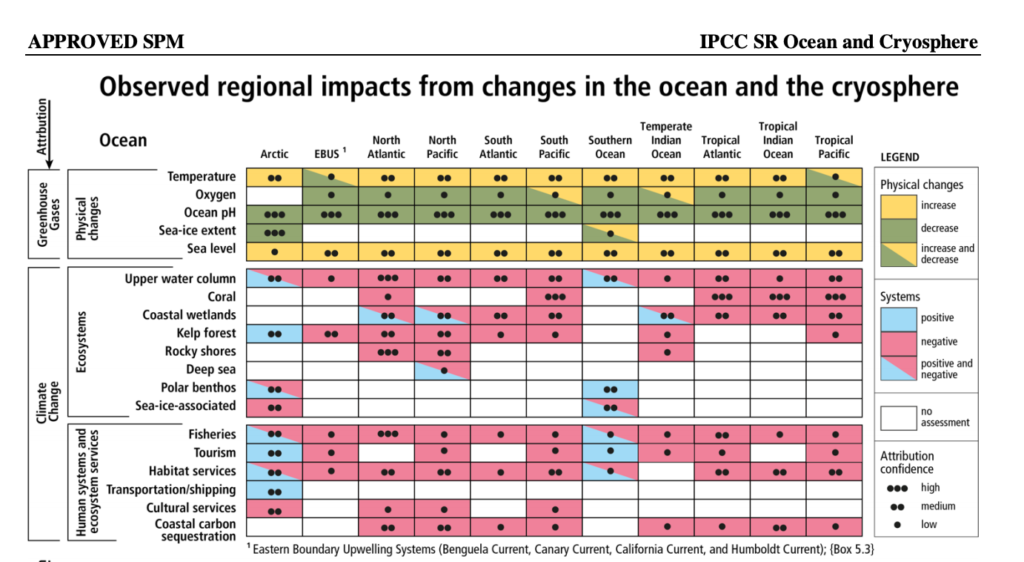

At first glance, the Arctic (left column below) looks like it may be benefiting from global warming, far more than other regions.

There are a lot of “blue” rectangles for the Arctic showing positive/beneficial changes from climate change – such as for shipping, kelp forests and tourism. By contrast, most other regions, especially tropical oceans, suffer a string of “reds” or negative/adverse changes in the IPCC study:

Summerkorn notes the changes in the blues and reds refer merely “to the given system or service”. More shipping and tourism, for instance, may benefit cruise companies and visitors but not necessarily people living in the Arctic and could even harm a marine environment at risk of more pollution and accidents.

“Disruptions to cultural and subsistence hunting activities from increased shipping compound climate-related impacts to people,” the report adds.

At the other end of the Earth, one of the most worrying findings by the IPCC is that a thaw of Antartica may already be “irreversible” because of an acceleration of ice flows, in the Amundsen Sea Embayment of West Antarctica and in Wilkes Land, East Antarctica.

“These changes may be the onset of an irreversible ice sheet instability,” it says. In the worst case, the report says oceans could rise 5.4 metres by 2300. With deep cuts in man-made greenhouse gas emissions, however, the rise could be limited to about one metre by 2300.

“Ice loss from Antartica is still the biggest cause of uncertainty,” in sea level rise, said Michael Meredith, of the British Antarctic Survey and the other coordinating lead author of the polar regions chapter. Global temperatures are up about one degree Celsius since pre-industrial times.

So far, most melting of Antarctic ice is caused by warmer oceans that are licking away the underside of glaciers and ice shelves on the edges of the frozen continent. “If we can restrict ocean warming the future of the Antarctic ice sheet is much more stable,” he said.

Among innovations, “Indigenous” is written with a capital “I” in the IPCC report, rather than as lower-case “indigenous” usually used by the IPCC. “It’s a huge step forward to … reflect Indigenous participation and contributions to knowledge,” Sommerkorn said.